Aidan’s Story: An Alternate Path to Braille and Literacy

Authors: Ann Adkins, VI Education Specialist, TSBVI Outreach Program

Keywords: braille, prebraille, literacy, struggling reader, “non-traditional tactile learner”, sensory integration, texture system, motivation, APB, tactile skills

Listen to the Article

I first met Aidan in 2014 during an onsite visit to Frenship ISD from the Outreach Program of the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired (TSBVI). His Teacher of Students with Visual Impairment (TVI), Sherry Airhart, had requested a student consultation for Aidan because she had questions about his progress with braille reading and writing. At the time of Sherry’s request to Outreach, Aidan was six years old and enrolled in a PreK program at Bennett Elementary School in Frenship, TX. Aidan is a student with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia (ONH) and Septo-Optic Dysplasia (SOD) and has no light perception or functional vision. He has a variety of medical issues including diabetes insipidus, hypothyroidism, hormone deficiencies, low cortisol levels, and fatigue issues. He also has very low muscle tone which affects both gross and fine motor skills. Sherry had been his TVI since he was two and a half years old.

Sherry completed a variety of suggested evaluations before the student consultation and worked with his educational team to complete his three-year reevaluation. The information she gathered showed that Aidan had a variety of strengths, especially in the areas of auditory memory, language and verbal skills, phonics, and rote spelling. His diagnostician noted that Aidan’s phonological awareness was in the superior range and that he had a strong desire to learn and please others. Results also showed that Aidan was struggling in many areas: concept development, tactile skills, orientation and mobility skills, motor skills, speech and language skills, social interaction skills, eating, coordination and balance. All of this information helped create a picture of a student with a variety of strengths and needs. It is not unusual for students with visual impairments to have such splinter skills, with strengths in some areas but deficits in seemingly related skills. As I prepared for the onsite visit, I felt that this might be a student similar to others I had seen. I was only partially correct.

When I visited Aidan at school, I observed a student who was receiving a very high level of support. I observed an educational program that emphasized concept development, sensory and tactile skills, and prebraille/beginning braille instruction. Aidan was provided with many activities of emergent literacy, as well as concrete experiences with a variety of real objects. I also noted the quality and variety of other tactile materials that were being used; they were traditionally accepted materials for students who are tactile learners.

I met with Aidan’s teachers, therapists, principal, and the VI Consultant from the Education Service Center (ESC). I also visited with Aidan’s parents in their home. All acknowledged and appreciated the comprehensive instruction Aidan was receiving. The VI Consultant at Region 17 ESC, who also served as Aidan’s Orientation and Mobility Specialist (COMS) and had worked with him since he was a baby, provided more information about the intensive VI instruction that he had observed for Aidan. It appeared that all of the skills that TVIs were supposed to teach were being taught, and that they were being taught in very effective ways with excellent tactile materials. Despite years of comprehensive instruction in braille and tactile skills, however, using an array of traditional methods and materials, Aidan had not made expected progress. He was struggling with learning even the most basic skills needed for braille and tactile literacy. Sherry and members of Aidan’s educational team questioned why he wasn’t reading braille, as did his parents. After reviewing all of this information, I also asked, why isn’t it working? Why hadn’t Aidan made progress? If he was receiving quality instruction with quality tactile materials, then why hadn’t Aidan acquired the skills needed for braille reading and writing?

While it appeared that Aidan was receiving the type of program that we hope all students with visual impairments will receive, what I noticed most when I observed Aidan were his sensory integration problems and difficulty attending to the activities, people, and things around him. This was true at both home and school. He seemed to be a happy young man, but he showed very little interest in things around him. He was described as being “in his own world”. He seemed happiest when he was singing to himself and beating rhythms on his chest. Any time that he was not being specifically directed by an adult, Aidan began singing, clapping, and beating on his chest. Sitting at a desk seemed difficult for him – he sat on his feet, turned and twisted in his chair, leaned back, flapped his hands, stretched, yawned, and engaged in what are often referred to as self-stimulatory behaviors. He did not appear to be aware of things around him unless his teachers specifically spoke his name. It sometimes took several requests to get his attention.

At home, Aidan spent non-engaged time playing on his bed, listening to music, and chewing on hard plastic toy animals. He also tapped the plastic animals on his teeth, usually to a recognizable beat, and liked snuggling and hugging with his sisters. He drank a lot of water but did not eat solid foods. His mother prepared his food separately in the blender so that it would be a soft, mushy consistency.

When I asked Aidan’s parents and his TVI what Aidan liked and enjoyed, it became evident that he had a very high need for sensory input. He liked swinging, cuddling, being in a closet, hugging, having a blanket, tapping his teeth or beating on his chest, and chewing on the hard plastic animals. Sherry provided some additional information:

- Aidan did not talk until he was three years old. His language was echolalic for several years after that, and at age six, it was still somewhat repetitive and not very meaningful.

- He was not walking when he entered the PPCD program at three. He began walking with support when he was four. He still wobbled when he walked.

- He disliked shirts with buttons, tags, or collars.

- Aidan had difficulty crossing midline and didn’t use both hands together in purposeful ways, except for beating on his chest. His hands were described as being “all over the place”.

- Aidan exhibited poor finger and hand strength, making it difficult for him to push the keys on a braille writer.

- He also had problems with identifying, spreading, wiggling, and isolating his fingers, especially his thumbs.

- He had difficulty with change and tended to perseverate on a few specific topics such as CDs.

- Aidan didn’t interact with other students.

This information provided a much clearer picture of Aidan. His sensory needs seemed overwhelming. I was concerned that it would be difficult for Aidan to attend to any instruction or develop any form of literacy until these sensory issues were addressed. I consulted with several occupational therapists (OT), shared information on sensory integration activities with his team, and arranged for a video conference between Lisa Ricketts, an OT at TSBVI, and the district OTs in Frenship ISD. There were follow-up visits from the TSBVI Outreach Program in 2015. I hoped that meeting Aidan’s sensory needs would begin to help him make expected progress.

Sherry supports Aidan during Special Olympics.

While some progress was made in addressing Aidan’s sensory needs, braille and tactile information still was not meaningful to him. He continued to struggle with tactile skills, literacy, and grade-level activities. I wondered if Aidan would, in fact, be a reader. Maybe he was one of those students who would be considered “an auditory learner”? Would Aidan ever be a braille reader?

After several years of instruction with traditional methods and materials, Aidan and Sherry were both frustrated. His family and school continued to ask why he wasn’t reading braille. So, at his annual ARD in September 2015, Sherry decided to make a change. Traditional methods and materials hadn’t worked, so she decided to try something different.

When I saw Aidan again in January 2016, I was absolutely amazed. He was reading braille whole-word signs! He was sitting up straight, his feet were flat on the floor, and his hands were on rows of whole-word contractions. He looked like a typical braille-reading student – but the contractions he was reading were not the dot configurations with which I was familiar as a TVI. The braille configurations were not made of dots! They were created out of a variety of different textures, things that were tactually familiar to Aidan, such as beads, buttons, beans, pieces of ribbon, and even a piece of an artificial Christmas tree. Sherry had created a system of textures for each letter of the alphabet and tied it to the braille code. Aidan was reading textures that represented all of the whole-word signs of contracted Grade Two braille! With this “texture system”, Aidan was able to read rows of “braille” letters, demonstrating many of the skills we expect of early braille readers, such as tracking across lines of braille, moving his hands from left to right, using both hands to explore lines of braille, etc. This unique system of textures was meaningful to Aidan whereas typical braille dots were not. Textures provided Aidan with the ability to learn and practice so many literacy skills. He was reading!

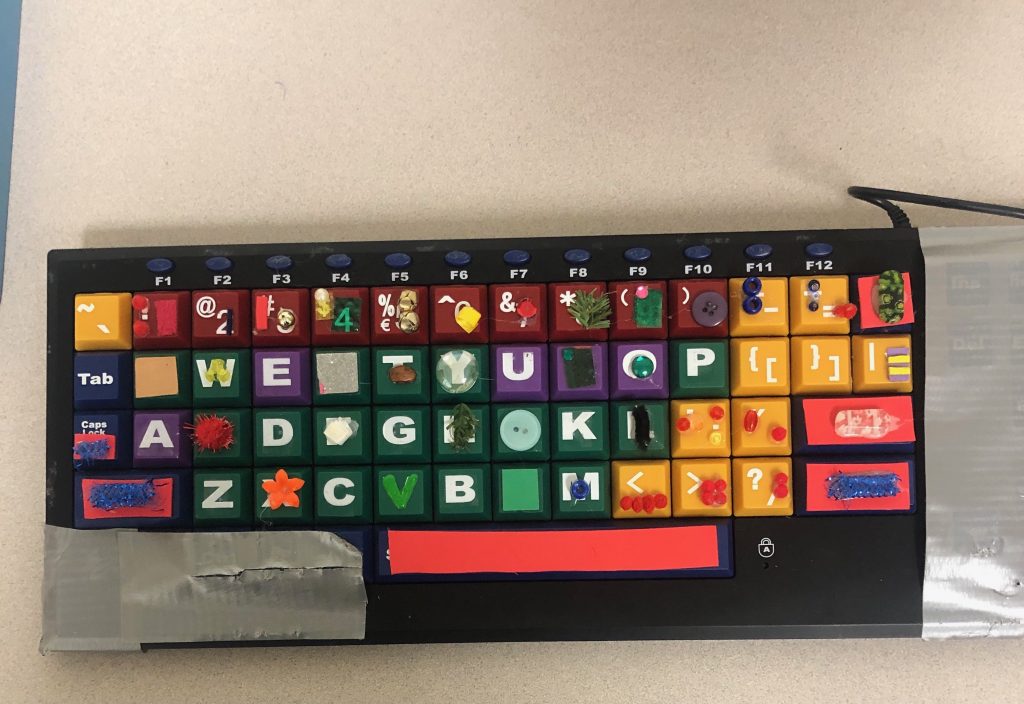

Aidan reads braille whole-word contractions written with textures.

Sherry explained how she created Aidan’s texture system and how it evolved over time: Aidan had heard her working on the computer one day and asked her what she was doing. He seemed really interested in the computer and what she was writing. Braille writing had never interested him, but Sherry realized that he was interested in the computer. As a former Life Skills teacher, she had always sought ways to help her students write their names. She wanted Aidan to be able to write his name as well. He had known how to spell his name orally for some time, but he had never been successful with the Perkins or Mountbatten braillers. So she decided to adapt a computer keyboard by placing textures on the keys. He still did not use his hands well (they were still “all over the place”), so she taped over all the keys except the letters for his name. She attached the new keyboard to her computer, turned on the sound, and was amazed when Aidan typed the letter “a”. He loved it! He quickly understood the 1-to-1 correspondence that a texture represented a letter. For the first time, he understood the concept of what letters meant! Within two weeks, Aidan was able to type his entire name.

Sherry adapted the computer keyboard with textures.

Sherry then began using the textured letters from Aidan’s name to create short words (“dad” was his favorite) which she attached to felt boards like the Wheatley Picture Maker from APH so that Aidan could read them as well as write them. He did! He understood that the textures were letters and that the letters made words. She began creating textures for all the keys on the keyboard and tied instruction to the braille code. She introduced letters gradually, depending on Aidan’s interests, and allowed him to master each of them before moving to another letter. She incorporated them into short stories and rhymes that he knew and enjoyed. It was only a matter of time before he was able to use the textured letters for reading and writing words, sentences, letters to his mom, and completing school activities. By 2017, Aidan was using textures for literacy activities in general education classes with his peers and for activities of the Expanded Core Curriculum (ECC).

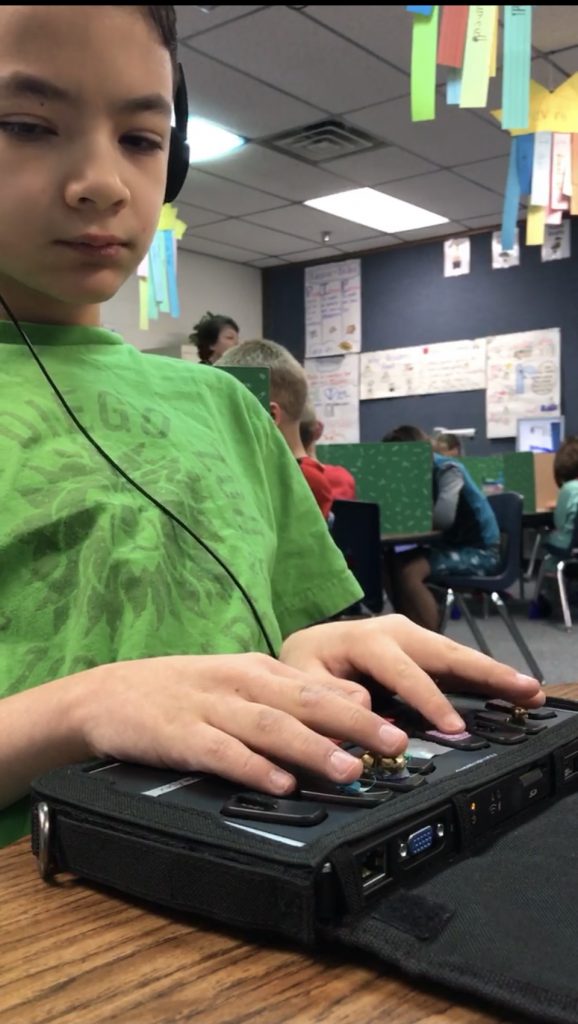

Sherry added textures to other materials and equipment as well—a calendar, clocks, rulers, a thermometer, a talking calculator, and eventually, a BrailleNote. Aidan began using textures, with either the computer keyboard or the BrailleNote, in general education classes to take spelling tests. Within the next few years, Aidan gradually transitioned to other tactile representations of braille symbols—braille cells of enlarged dots made of different materials such as Velcro and puff paint. In 2018, Aidan’s New Year’s resolution was to learn regular braille. In May of that year, Sherry began transitioning him to jumbo braille. Again, Sherry introduced letters gradually, and she combined them in stories and worksheets with the puff paint letters he already knew. Once Aidan was successfully reading jumbo braille, he was ready for regular braille. By March 1, 2019, Aidan was reading and writing contracted Grade Two braille! Aidan is now a confident and successful braille reader of traditional braille materials.

Aidan uses a BrailleNote to take a spelling test in his general education class in 2018.

Textures were the beginning of APB, Aidan’s Path to Braille. APB was more than just Aidan’s path to braille, however. It influenced many other areas of Aidan’s life too, not just his literacy skills:

- He became more focused and attentive, at both home and school.

- His O&M skills and independent living skills improved.

- He developed better posture and sat up straight.

- He seemed more interested in learning and asked for adapted materials.

- His social skills, language and conversation skills improved.

- He became more aware of people and things around him and participated in grade level activities, including social interactions with peers.

- His eating skills improved. In the fall of 2018, he ate pumpkin pie for the first time when he helped make it with his class. He even began eating and choosing food in the school cafeteria.

- He seemed to process information more quickly and was less dependent on auditory prompts.

According to Aidan’s mom and his COMS, APB changed everything. It unlocked his world!

“Sherry invented a texture system that has unlocked something in Aidan’s brain! He is actually comprehending the meaning of reading now.”

Aidan’s mom

“Sherry’s system has changed Aidan’s world!”

Steve Boothe, COMS, Region 17 ESC

When asked to summarize Aidan’s Path to Braille, Sherry said that APB was not started as a system to replace braille but was “an opportunity to gain the concepts of reading and writing”. It is:

- Individualized and student-centered

- Interest-based, built around what was motivating to Aidan

- Designed around his strengths (auditory skills are Aidan’s strength, so Sherry tied instruction to that)

- Evolving! It had to change in order to meet his changing interests and needs.

- Flexible, but systematic

I also asked Sherry for her suggestions for other teachers and TVIs:

- Know your student!

- Emphasize what he can do, not what he can’t do.

- Observe how he learns, how he uses his hands, and how he approaches things.

- Determine what is motivating to him and use that. Consider his interests as well as his strengths and needs.

- Break instruction into small steps (task analysis). It may really be baby steps, depending on your student.

- Provide as much time as your student needs to master a skill before moving on to another.

- Be systematic and consistent.

- Do the easiest braille letters first (a, l, k, etc.).

- Be willing to try “whatever works”.

- Don’t be afraid to ask for help.

- Look for different solutions! If something isn’t working, try an alternate path.

- Think outside the box!

- Never give up!

Summary/Conclusion:

Aidan actually began his path to braille literacy long before I saw him in 2014. We discovered that Aidan had actually heard and internalized much of what Sherry had been teaching him during those early years about the braille code, basic concepts, dot counts, tactile skills, etc. He didn’t have the ability to communicate that at the time, however. Once he had something meaningful to which he could attach that information, he was able to use that stored information about braille. The textures were very meaningful to Aidan, both tactually and cognitively, allowing him to make the progress his team had wanted.

Aidan’s success was the result not only of Sherry’s dedication, perseverance and creativity, but also her understanding of what was important and meaningful to Aidan. She recognized the gap between his oral functioning and his tactile/sensory performance, and she felt that he could do more. She saw his potential learning ability and knew his strengths. She was also willing to “think outside the box” when traditional methods of instruction didn’t work. She didn’t give up. She created a program of instruction based on HIS individual strengths, interests, and needs. It worked! Sherry continues to teach Aidan to use his tactile skills in meaningful ways and provides him with experiences that make other abstract concepts meaningful as well.

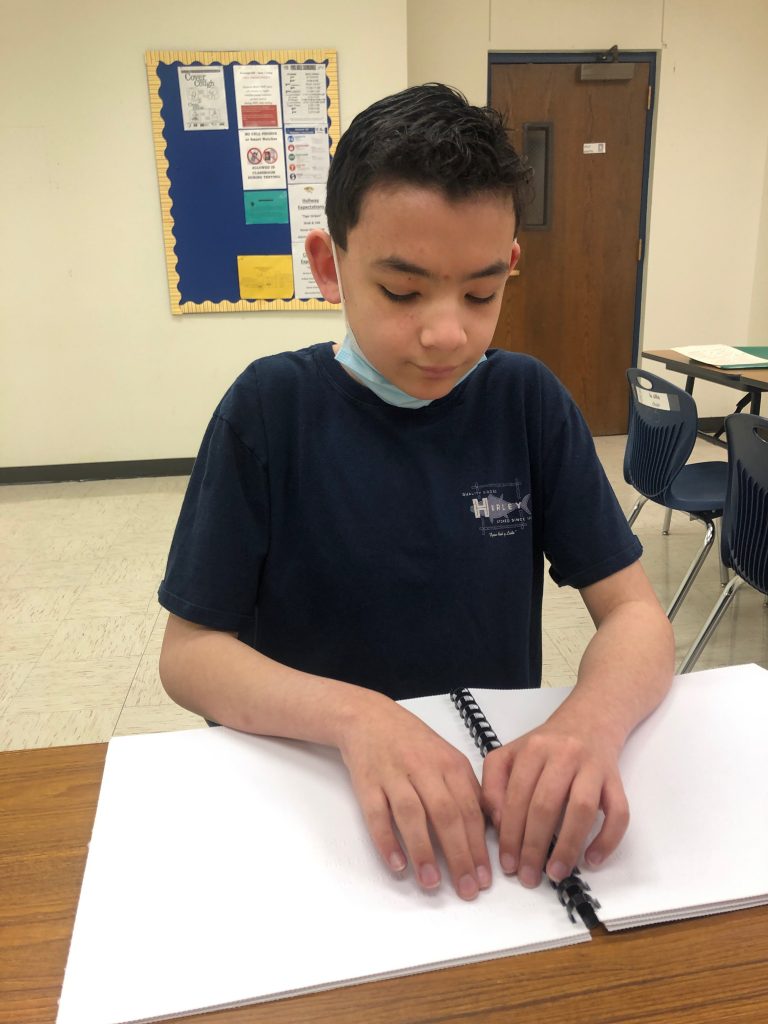

Aidan now reads contracted Grade Two braille!

We know that there are other students like Aidan—non-traditional tactile learners who have difficulty learning abstract representations like braille. Sherry and Aidan have taught us that there IS more than one way to learn and to teach, and that a creative approach can open a world of literacy to students who are non-traditional learners. We hope that Sherry’s unique and innovative approach to braille instruction will help other students and their teachers discover their own path to literacy. There is an alternate path to braille and literacy!

“If a child can’t learn the way we teach, maybe we should teach the way they learn.”

Ignacio Estrada